According to a Christian understanding, Church and State should coexist in a harmonious complementary relationship. But debates as to how such a relationship functions and where to draw the boundaries between one and the other “power” are as old as Christianity itself.

At the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church's magisterium shifted from the Church-State dichotomy to emphasizing the role of Christian believers in civil society and in the international human family. Hitherto, however, the Holy See sought to manage the relationship with treaties or concordats aimed at protecting the liberties of Catholics and to accord the Church institution with certain advantages. This was especially true in countries where Catholicism was the majority religion.

One such country was Poland, which, after having been partitioned between three Europeans Empires at the end of the eighteenth century, emerged as an independent state in 1918. Even after the end of imperial rule, a Josephist (or Josephinist) ideology remained among the civil bureaucracy. Named for Austrian Emperor Joseph II, this rationalist Enlightenment theory relegated religion to the private consciences of believers. Anything touching on religion in the public sphere was to be regulated by state functionaries as opposed to Church officials.

Even the Concordat between Poland and the Holy See, ratified in 1925, was fraught with diverging interpretations. Prominent Polish statesmen considered certain guarantees to be formal courtesies lacking in juridical content. In their (Josephist) view, the clergy were like civic functionaries that should be submissive to government policy. This is why they demanded that the Concordat make the bishops and major clergy swear an oath of loyalty to the State upon taking office.

The Church interpreted this oath as a promise of loyalty to the institutional state rather than to a particular regime, government, or policy. Additionally, the Holy See conceived the oath to be that befitting the office of a bishop/priest; a loyalty which did not contradict Divine Law, Church Law, or his moral duty to defend from excessive state pretensions. Marshall Piłsudski’s authoritarian regime, which took over the State in a 1926 coup, considered the oath in maximum terms. Thus, it altered the wording, for Orthodox bishops, from an oath of loyalty to one of obedience.

The history of the Second Republic is often obscured by the history of Communist and Post-Communist Poland. This is more so when we think of the role of the Church and believers in Poland. For instance, not well known is the extent of the hostility by officials of the Sanacja regime to the influence of Catholicism in society.

Authoritarian regimes seek ever greater control over every aspect of the nation and invariably find themselves in competition with the Church, especially if the clergy and laity are fulfilling their prophetic mission to speak truth to power. Such regimes seek to denigrate the Church’s moral authority and sometimes even attempt to usurp its preaching and teaching role. Secular officials tell the faithful that good Catholics are those who respect the civil leadership. Those who challenge are labelled with simplistic slogans. The regime activates useful idiots as well as honourable but naive patriots, who hesitate to believe evil of the leadership. In more recent contexts, new forms of Joseph[in]ism have made a comeback.

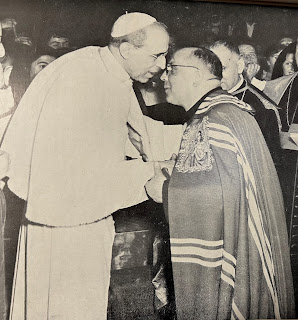

The following document was presented to Pope Pius XI by the Primate of Poland, Cardinal August Hlond, in March 1932. It certainly shows its age and mindset of the time. And yet it is valuable to understand s the historical situation only seven years before the beginning of the war which, de facto, ended the existence of the Second Polish Republic.

SECRET INFORMATION

on the Religious-Political situation in Poland

Rome, 14 March 1932

For some time now, unfortunately, one notes a certain tension between the Government and the Church in Poland. The causes? Government circles blame the Church, asserting that the Episcopate is aggravating the Government and that the lower Clergy is in political opposition to it. How do things stand in reality?

1- THE ATTRIBUTES OF GOVERNMENT CIRCLES

In the Government and its party, which makes up the majority in the legislative chambers, there are undoubtedly Catholics. However, the majority of the government’s parliamentary coalition is made up of people who are religiously indifferent and positively adverse to Catholicism. There are Socialists, free thinkers, sectarians, apostates and Freemasons, not to mention Protestants, schismatics and Jews. Among the Catholics, then, there are those who come from Socialism, which they remain infected with especially in those that concern public life and relations with the Church. This is also the case of Marshal Piłsudski.

The Government of today, with a few exceptions, is composed of legionary officers of not very high intellectual culture and of poor political preparation. Their government is dictatorial in principle and their way of perceiving and taking things is military. They do not make much effort to conform to the European standards and especially do not see the need to do so in internal administration.

2 – POLITICAL IDEOLOGY OF GOVERNMENT CIRCLES

The idea of the State has not yet crystallized in the government’s program. It oscillates between fascist and bolshevik conceptions. The omnipotence of the State is however one of the cornerstones of the present political system. The citizen, the individual, no longer counts. The family is almost excluded from the influence on the spirit of education in state schools, which is based on the cult of Marshal Piłsudski. Nobody has an idea of what normal relations with the Church should be. Government spheres feel harassed by the strong position of the Church, whose authority and influence are growing.

In particular, within the government’s parliamentary coalition there are various tendencies, strong divergences of ideas, and even struggles which become livelier and sharper as the personal influence of the Marshal decreases [due to age and infirmity]. Catholics in the government’s coalition have been unable to exert sufficient influence on the direction of affairs. And thus, unfortunately, the tendency within this coalition is secular. This explains a sad fact: the Nation remains faithfully attached to the great Catholic traditions of its past, called by Providence to successfully implement the Christian conception of the State. Nevertheless, it is generally governed in a sectarian sense and pushed towards a non-Christian future. The only obstacle in the way of the rush towards secularism is the firmness of the Episcopate.

One of the characteristics of the program to secularize the life of the Nation is a tendency to avoid open conflict with the Church, which would have serious political consequences in Poland. Conflicts with the Holy See are therefore carefully avoided and the letter of the Concordat is generally observed, thus avoiding persecution of the Church. At the same time, however, attempts are made to gradually implement the secular program, in ways that are invisible but insidiously effective. The soul of the Nation is being poisoned with a sectarian spirit. Its moral strength is being shattered with free rein being given to every kind of vice. The existence of the family and the institutions of the Church are being threatened by laws and decrees. Ways are being studied to undermine the authority of the Episcopate. Its work is being interfered with, the clergy is being harassed and accused of being opposed to the Government and an enemy of the State. [...]

4 – SECULARISM IN POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION

In the government, the political administration, in diplomacy, and in the army, free thinkers, atheists, bigamists, and apostates are given preference. Practicing Catholics are gradually kept back under one pretext or another. In general, personnel changes are unfavourable to Catholics. [...]

Political authorities usually look askance at State employees maintaining friendly relations with the Church. Several employees at the Ministries were expressly told that, to advance in their career, they should associate less with priests. In circles dependent on the Government, that kind of corruption reigns. In order not to get into trouble, one must maintain an unfavourable or at least reserved attitude towards the clergy. Whoever demonstrates the ability to harm the Church is protected against any misfortune. For this reason, State employees do not belong to Catholic Action and are beginning to absent themselves from the Marian Sodalities.

The correspondence of the bishops is secretly monitored, and the clergy are also meticulously monitored. The Governors’ political offices have introduced card files for each priest. These record not only their political conduct but also their private and priestly conduct, naturally based on unverifiable police reports and complaints of the clergy’s adversaries. Catholic Action and all the Associations that belong to it are specially monitored. Control is also extended to the confraternities, third orders, Marian sodalities, etc.

Since I repeatedly complained about the harassment suffered by Catholic organizations and their members, last November the Minister of the Interior issued a circular forbidding any harm to Catholic Action. Since that time the authorities have harassed it a little less. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the pro-government associations have intensified their work. They never tire of denigrating Catholic organizations, especially those for youth and charity. Even missions for the unemployed, introduced in the Dioceses following the Encyclical of His Holiness, were molested and persecuted by state organs, in various places.

The Government does little or nothing to hold back the flood of immorality, indeed it seems to encourage it. The ministerial commission for monitoring films permits real indecency to pass. Bad writers, who devastate [public morals], are supported and favoured. With the permission of the Minister of the Interior, eugenic consultation offices are being set up, whose purpose is to teach the most effective methods of contraception.

5 – THE SPIRIT OF SECULARISM IN EDUCATION

It is true that in accordance with the Concordat, religion continues to be taught in schools, but it is also true that there are continuous attempts to give the rest of the school a secular imprint.

Firstly, there are several cases where school authorities reduce the hours of religious teaching without reaching an agreement with the Bishops.

Practicing Catholics are systematically eliminated from offices of higher education and are replaced by unbelievers, Protestants and defrocked clergy. The number of unbelievers is growing in the ranks of teachers and professors, and they are always favoured. A few weeks ago, at the headquarters of the Superintendent of Education in Poznań, the Association of Freethinkers for School Employees was officially founded. This year, I noticed that, in my Archdiocese, atheist teachers are already beginning to be in the majority in certain secondary schools, where only good Catholics taught five years ago.

Teachers are forbidden to take part in Catholic youth associations. It is viewed with displeasure if they are on good terms with the clergy. The spiritual retreats that I organize annually for teachers are frowned upon. And they were not pleased when, last New Year's Eve, I presented to school officials, professors and teachers of the Poznań voivodeship (about 8,000 people) a special annotated edition of the Pope’s Encyclical on Christian Education.

They have started harassing the Marian Sodalities that are thriving in the middle schools. Instead, they organize clubs of various kinds in the same schools, in which unfortunately they propagate bad attitudes. They force the youth of the middle schools to read and comment on modern literary works, some of which are even pornographic, especially in high schools for girls.

A large-scale program is being launched against the Catholic character and spirit of Polish scouting, which hitherto has distinguished its ranks. Unfortunately, this program has already made inroads into the female section.

6 – SECULARIST TENDENCIES AMONG POLISH ÉMIGRÉS.

Unfortunately, the Government agencies are also bringing secularism to Polish émigrés, as I witnessed among emigrants in the United States, Brazil, London, and especially in France.

So far, in [France] has not been possible to have the schools organized by the Polish Government to be administered in a Catholic spirit. On the contrary, these schools are conceived as purely atheistic. The teachers sent there from the homeland were convinced not to teach religion and not to have contact with Polish priests. Only now, after my recent interventions, has the Polish Government promised to organize religious education in those schools. Certain Polish consular representations in France never weary of fighting Catholic organizations among the emigrants. They often hindered the work of Polish priests, who are carrying out a very important pastoral mission.

7 – THE “AGGRAVATING CONDUCT” OF THE BISHOPS.

Far be it for me to assert that everything the Government does is bad. Neither do I intend to infer that the Polish Government is always inspired by hatred towards the Church. I also willingly recognize all the good that it does for the Church. And I do not miss an opportunity to express my satisfaction and gratitude to the representatives of the State for the services they provide to Religion.

But is it any wonder that the Bishops, faced with anti-religious tendencies and the facts, take steps to defend the faith, morality, and rights of the Church? All these steps are now described by the Government and pro-government circles as “aggravating behaviour” and as a cause of tension between the two powers [Church and State].

More than once, the Government and its parliamentary coalition have invoked the principal of State sovereignty to convince the Bishops they must not interfere in any way in what the Government does. That is, they would like the Church to be completely uninvolved in what the State legislates and decrees, even if the laws, decrees, and orders intrude into the religious sphere, offend morality, and infringe upon the Church’s rights. Whenever the hierarchy does anything to oppose the wave of secularism, in such cases, we hear cries that the Bishops do not respect the State and are unfaithful toward it.

They convinced Marshal Pilsudski of this theory, and he became fixated with the idea that the Bishops hinder the work of the Government and show disrespect toward it. He usually expresses this with the motto that: ‘the Bishops want to bring back the Middle Ages to Poland.’

The Episcopate, on the other hand, understands very well that it must guard against even the appearance of being influenced by the opposition parties. The episcopate knows that that its actions, especially concerning the Government, must be well-founded, serious, dignified and respectful. And it is worth noting that, for years now, the Episcopate’s collective statements have been redacted in the style of calm gravity. Sometimes they are strong, as in questions of matrimony, but they are never offensive or lacking in respect. Except for a few exceptional (well known) cases, even the personal pronouncements of the Bishops are anything but exaggerated. Rather than a lack of respect for government authority, they might be faulted for not presenting Catholic doctrine in relation to the errors and unhealthy tendencies of the modern age with sufficient clarity.

I also believe it is my duty to point out that the Episcopate is in constant and cordial contact with His Excellency the Apostolic Nuncio, who is perfectly aware of what is happening in Poland and merits the full trust and great veneration of the Bishops.

8 – “THE POLITICS” OF THE LOWER CLERGY.

Pro-government spheres accuse the lower clergy of not being faithful to the Government according to the meaning of the Bishops’ oath. In the last parliamentary debates on the ecclesiastical issues (mentioned above), it was stated with regret that eighty-five percent of the clergy is not on the Government’s side.

If it is a question of convictions and feelings, I believe that not even 15% of the clergy have confidence in the present Government or hope that, over time, the positive elements in pro-government spheres will prevail in lending Christian direction to politics. The rest [remaining 85%] do not have confidence in the Government, especially because of the tendencies and facts mentioned above.

If we now take into consideration actual politics, it should be clarified that the phenomenon of the political priest is becoming increasingly rare. From year to year the number of priests who take an active part in political movements is decreasing. While previously there were thirty, forty, or more priests as deputies, in today's Parliament there are four priests in the government’s coalition and one in the national one. It is true that a certain number of priests, especially in the former Germanic regions, continue out of habit to belong to parties that have remained in opposition following the revolutionary events of 1926. But in general, this is a personal membership that does not try to propagate the party and without actions the oppose the Government.

Increasingly rare are priests who take an active part in politics to the extent permitted by ecclesiastical law and the laws of the country. Exceptional are the cases in which a priest abuses his office for political propaganda or fails to show obedience to the Government or to be faithful to the State. In such cases the Government invariably brings criminal charges, but all the cases end with acquittal, except for some singular cases concerned with the national minorities.

The Government’s irritation is based on fact that the clergy in general do not accept the government party’s policies, which naturally has a strong impact on the behaviour of the population.

[The Government] misinterprets the Bishops’ oath and thus accuses the Clergy of being unfaithful to the Government and the State, because they belong in part to political groups other than the pro-government coalition or because, obeying the Bishops’ orders, they preach against the dissolution of marriage, against infanticide [abortion], against the decline of the social morals, etc.

For example, the Governor of Poznan complained to me that, among my priests (there are a thousand of them), there are some who are not loyal to the Government. But when asked for concrete facts, he was never able to provide me with a single one that might be incriminating.

9 – CONCLUSION: THE REAL CAUSE OF THE “TENSIONS”

Leaving aside the well-known mistakes of certain Bishops, which in no way can be blamed on the collective Episcopate, if there is tension between the Church and the State in Poland, it is explained by the furious indignation of Freethinking Circles following their moral defeat on the issue of marriage. The strong protest of the Nation against the proposed marriage law, caused by the strong statements of the Bishops, was the hardest blow endured by the secular politics of the pro-government party in Poland. Hence the anger.

In fact, until November of last year, there was almost no talk of bishops or priests being politicians. Then suddenly they were all declared politicians, not deferential to the Government, unfaithful to the State, violators of the oath. This is a reaction and revenge of wounded sectarian hatred.

In conclusion it is important to note:

a) The policy of the present Government involves manifestly secularist elements which prevent tasks of the State from being carried out in due conformity with Christian precepts.

b) It is the task of the Church and of Catholic Action to save the Polish soul from sectarian infection. The Church must find a way to do this while respecting the Government, maintaining fidelity to the State, and preaching to Catholics respect and obedience to public authorities.

c) The work of the Church, insofar as it corrects the aforementioned secular tendencies, is frowned upon by the Government and pro-government circles, and causes that state of unease which is called tension between the two powers.

And as to remedies? The Government seems the remedy in the Church ceasing to watch over the spirit of the Nation and not opposing any legislative or administrative acts, even when they are contrary to the Law of God and the Church. This is impossible. Instead, I believe that today's annoyance and other tensions can be alleviated and partly prevented:

a) by coming to a fair solution in the unfortunate disagreement between some Bishops and the Government, [...];

b) by clarifying the principles of the Christian concept of the State and the relations between the two powers. Such problems are being totally ignored even by Catholic politicians;

c) by persuading the Government to make the appropriate arrangements with the Episcopate before making decisions or establishing draft laws or decrees on mixed [Church-State] matters, such as Catholic schools, religious hospitals, marriage, etc.;

d) by instilling in Catholics respect for the authorities of the State and obedience to the just laws and decrees of the Government;

e) by continuing to draw the clergy away from any active participation in politics;

f) by ensuring that no Bishop takes personal decisions in his relations with the Government which could have consequences for other Dioceses. Uniformity of conduct must be safeguarded in the interest of the common cause. Some indication from the Holy See in this regard would save us in future from certain troubles, such as have unfortunately already occurred, for example, regarding the Organizations of Catholic Youth.

Hlond's original report, typewritten in Italian, is in the Archive of the Second Section of the Papal Secretariat of State: ASRS, AES, Polonia, period IV, pos. 144. Cardinal Pacelli also sent a copy to the Apostolic Nuncio in Warsaw: AAV, Arch. Nunz. Varsavia 257.