|

| Saint Paul's at Ellice & Vaughan |

Saint Paul’s College

To assume the direction of the College, Sinnott turned to the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) only after the English-speaking Jesuits declined to take up his offer. As a result of their refusal, he became cold toward the Jesuits, and there was even talk of their leaving Winnipeg altogether. Father Erle G. Bartlett, stationed at Saint Ignatius Parish, helped to heal that rift. Bartlett befriended the Archbishop and encouraged him in his plans to improve the College.

|

| William Hingston, SJ |

|

| from SPHS Archive |

| |

|

At the end of February 1934, the Provincial Superior made his first canonical visitation (inspection) of the College to observe the progress of his confrères first-hand. He had the occasion, in his letter to the Father General of 12 March, not to regret his choice of Holland, whom he described (in Latin) as

The other members of the Jesuit team were also playing essential roles. McDonald “successfully introduced discipline which hitherto had never existed.” A new spirit had begun: “everyone is teaching better, the students are working harder, and this was accomplished by only four Fathers who have already given the College a Jesuit aspect.” This “aspect” included the setting up of a Marian Sodality, the Apostleship of Prayer, and the practice of frequent Communion.

College Debt

Now that the Jesuits had a second mission in Winnipeg, Hingston wanted to give up Saint Ignatius Parish. Holland and his locals confrères opposed this. They warned the Father General that it would be a grave error, since the College needed local friends and benefactors and could not exist as a stands-alone affair. Holland believed that, if the parishioners of Saint Ignatius would take up the cause of the College, their attitude would spread to the other parishes of the Winnipeg Archdiocese.

In the spring of 1935, a loophole was discovered which served as a bargaining tool: Although Sinnott had transferred to college according to civil law, he had failed to secure the necessary approval from Rome, required by Canon Law. Sinnott had sent the request to the Papal Embassy (Apostolic Delegation) in Ottawa which forgot to send it on to Rome. On 4 April, the Father General wrote Cardinal Bilsetti (in charge of the Vatican education department) explaining that Hingston had been remiss about this and other matters, so he sent a priest directly from England to replace him.

In May 1935, the new Provincial Superior, Father Henry Keane, confessed to the Archbishop that the Jesuits would have to withdraw, as they were unable to continue at the College under the current circumstances. Sinnott responded furiously, on 10 June, that he wanted them to fulfil their contractual obligations:

“I shall be very sorry to see the Jesuit Fathers leave St. Paul’s College, for they have done excellent work and I am much pleased with them. But with regard to the financial situation I have been grievously disappointed.”

The College’s creditors had forced the Archbishop to pay the interest on one of the loans, and Sinnott demanded a decision from the Jesuits within three weeks.

Keane advised Ledóchowski to obtain Vatican permission to leave the College unless Sinnott helped with the debt. The Provincial did not think the Archbishop would let them go because, as he wrote to the General, “under our direction the College has flourished, the number of students has increased, it recovered its fame, it has achieved successful exam results once more.”

On 4 July, the General responded to the Provincial that one could manage such a debt under the conditions of the Great Depression and told him to remind Sinnott of his promises of $10,000 annual support. The Jesuits were prepared to remain but not to shoulder the whole debt. Ledóchowski even expressed doubts about civil legalities because, under English Common Law, a contract was invalid if one of the conditions (i.e. annual support) was not met. When questioned, however, Father Hingston was vague about exactly what Sinnott had “guaranteed” in the way of financial support.

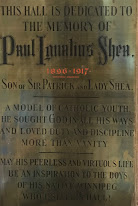

On 26 September 1935, the College Rector sent his annual report to the General in which he touched the misunderstanding between the Provincial and the Archbishop. John Holland explained that Sinnott was poor and his cathedral was in heavy debt. The Archbishop was under a false assumption that the Upper Canada Jesuits were wealthy and would take care of the debt. And Father Hingston had been led to believe that the Patrick Shea had made a large bequest to the College.

Holland identified the root of the problem in the expectations placed upon the Sheas' on-going generosity. He felt that the Archbishop had been too forceful with the Sheas before the Jesuits assumed the college mantle. It was Margaret Byrne Shea, rather than her late husband, who given to charitable works and who had taken an interest in Saint Paul’s. Although she had cooled toward Sinnott, she continued to be close to the Jesuits and promised $25,000 for the College, provided that none of it went to the Archbishop.

A Mistake to Give it up

With the debt looming, the Jesuits had to carefully consider their permanence at the College. In the autumn of 1935, several Canadian Jesuits sent their views to the General Superior. On 26 September, John Holland wrote:

“The Fathers who are here are all convinced that there is a splendid future for St. Paul’s College and that it would be a mistake to give it up. They are willing to make every sacrifice, as they have been doing, to retain it. … The enrolment has increased considerably this year…The College is becoming increasingly known and especially its reputation for order and discipline being spread. … The Archbishop is very anxious that the Jesuits keep the College. He has been quite pleased with the progress that has been made and has shown himself ready to help us all he can.”

On 17 November, Father James Carlin, Prefect of Studies, told of Holland’s extraordinary skills:

“The Reverend Rector shows great wisdom and discretion in all his dealing and due to his untiring efforts, the College is being spoken of most highly by the people of Winnipeg and especially by His Grace [Sinnott].”

Carlin had a great vision for the College’s future, which included a training centre for Jesuit recruits:

“To my mind this is the very best opening we have in Canada. We are making every possible effort and sacrifice to finance and we can do so, if given time. … Our affiliation with the University permits a theological faculty with degrees of Divinity. If we established this course we would become the Innsbruck of Western Canada. A Canisianum would prove most popular to the western bishops who are trying hard to conduct small seminaries of their own. The West is our field, if we establish immediately.”

In May, Father Keane came from Toronto to make an official visitation. In his report to Rome, he noted that, in spite of many difficulties, the College had increased enrolment and had been successful with exam results and with human formation. In addition, “religious formation and solid teaching of Christian doctrine were constantly required “neque negligatur ad veram et christianam urbanitatem institutio (so that formation of true Christian manners be not neglected) –Letters of Saint Ignatius Loyola, 386.” He believed that “the experiment [of running Saint Paul’s] promises to be a solid success in every way.”

In his 22 May letter to Father Ledóchowski, Father Keane recounted an event incident that had occurred a few days previously. The Jesuits had invited Archbishop Sinnott to lunch and, the following day, Sinnott returned the compliment, after which he had a long conversation with the Jesuit Provincial. The Archbishop behaved very amicably, never waning in his praise for the College and the Jesuits. “Above all, he praised Fathers Holland, Kelly, and McDonald, who had “transformed the students for the better,” which had result in an increase of financial support from their families. These positive results bode well for the College’s future.

Keane was given the opportunity to explain the financial situation, which greatly surprised Sinnott. While the Jesuits were not in a position to pay the debts, the Provincial Superior argued that, given time and with a new loan, they would be able to do so. The Archbishop “begged and pleaded” for the Jesuits not to leave the College, which he characterized as “the greatest misfortune.” As to Vatican permission for the canonical transfer of the institution, Sinnott laughed and said that the matter had been bungled by the Apostolic Delegate. The Jesuits did not need to be concerned because “they cannot refuse to grant it.”

In September 1936, Father Holland sent his annual report to the Father Ledóchowski. Father Carlin’s death had dealt “a great blow to the College,” Holland described his late confrère as “a splendid religious, a capable Prefect of Studies and a tremendous worker.” From his deathbed, Carlin expressed but one regret: that he would not be able to help the College by carrying out his beloved duties. On a positive note, friendly relations with Archbishop Sinnott had been completely restored, as the Rector noted:

“He has done a great deal for us and he is certainly interested in the welfare of the college. I think that the interview that Reverend Father Provincial had with him during the visitation helped to clear away certain misunderstandings which had existed up to that time.”

Material and Spiritual

|

| Charles Kelly, SJ |

According to these reports, the financial standing was improving and, for the first time, the interest on the loans was paid in full. Over half of the 271 students were receiving discounts, bursaries, or scholarships. Relations with Archbishop Sinnott were very good, according to McGarry, largely “due to the prudence of Father Rector.” Sinnott took an interest in the College and helped in various ways, including a Diocesan collection on Pentecost Sunday, to pay the College taxes. Father Kelly wrote that Sinnott “is more of a help to us than any other Archbishop or Bishop is to any of the other Jesuit Colleges in Canada.” But he was very conscious of his position and dignity: “he wishes all and sundry to realize that he is the Archbishop of Winnipeg.” Sinnott could be impatient but also magnanimous and expected others to show him gratitude.

The internal spirit of the Jesuit community was of primary importance to the order. Indeed, engendering a positive, united, and religious attitude was Holland’s recipe for a successful endeavour. Both he and Keane wrote that the “spirit of observance of the rule, laboriousness, charity, and cooperation abide.” Kelly could not “commend too highly the spirit of charity and piety that marks the life of the Community. … The spirit and mutual trust among the Community at St. Paul’s is noted in this Vice-Province and we wish to keep it that way.” And finally, in his 31 December report, McGarry noted: “Gubernatio hujus domus suavis est, sed non ut in laxitatem labatur. (This community is governed lightly but not in a way that falls into laxity.) Indeed, Holland monitored religious discipline daily so that that Jesuit community life remained a concrete reality.

|

| Sinnott blesses Shea Hall cornerstone, 1932 |

Father Keane’s successor as Provincial Superior, Father Thomas Mullaly, informed the General Superior that he and his counsellors were opposed to the expansion unless $100,000 could be found to cover the costs. Meanwhile, the Archbishop went to Rome to perform his ad limina visit and to present his plans to the new Pope, Pius XII, and the Roman Curia. First, he met with Monsignor Ruffini of the Vatican education department, then with the Jesuit General, who approved the matter in principle. On 11 June 1939, Sinnott addressed two letters letter to the Pope. In the first letter, he sought the Pontiff’s blessing for the expansion of the College upon which he lavished high praise:

“This College is my joy and my pride. It is now under the care and direction of the Jesuit Fathers and I am thoroughly satisfied with their work. I am wholeheartedly behind them and I will not be content until every Catholic boy under my jurisdiction receives his higher education in this institution.”

The Archbishop asked for the Jesuits be allowed to borrow $100,000 to finance the venture, and the Pope entrusted the matter to his Secretariat of State. On 8 July, Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini (the future Pope Paul VI) asked the Jesuit General to accede to Sinnott’s desire, provided that he thought it “wise and opportune.”

Meanwhile, the Winnipeg Jesuits came up with a counter-offer. Instead of a large and costly extension, they proposed adding six classrooms which would require only $45,000. Sinnott agreed to the more modest extension and gave his solemn assurance that he would help with fundraising. On 6 June 1939, Father Ledóchowski approved the revised plan after obtaining permission from the Vatican department for religious orders. On 15 July, he informed the Secretariat of State that the matter was arranged, and Montini gave Sinnott the good news on 21 July.

Alfred Sinnott’s second letter to the Pope, presented on 11 June 1939, was also connected with his plans for Saint Paul’s. He was looking for a mark of success and a visible sign that the institution (and its founder) enjoyed papal approval. The Archbishop wrote:

“I crave a mark of benevolence and paternal encouragement that will never be forgotten in the years to come. I ask that Your Holiness will make a gift to the College of an oil painting of the great apostle St. Paul. I do not desire an original, but rather a copy of an existing picture which will be inspiring to the young men who frequent the institution.”

|

| Della Porta's original |

“It was with particular pleasure that the August Pontiff learned of the growth of the College and it is His confident hope that this gift which He deigns to bestow at this time, […] may, indeed, be a source of real inspiration to the students of the College.”

The additional classrooms were completed by the end of 1939. In December, Sinnott sent effusive thanks to the Pope “for the magnificent painting,” together with a notably large “Peter’s Pence” offering for that year. He also agreed to a new contract with Jesuits, which came into effect in April of 1940, in time for his episcopal silver jubilee.

Even with the additional classrooms, with almost 400 students, Saint Paul’s was outgrowing its downtown campus on more than one level. Father Francis Smith’s report, from the summer of 1938, noted that Holland, who had been marvelous in dealing with the problems of the early years, was lacking a vision for the future. Holland, Kelly, and McDonald were not intellectuals and placed a great deal of emphasis on sporting activities. Also, the students of the High School were excelling at greater rate than those of the College, perhaps because the Rector himself taught the former and subconsciously gave them preference. It was time for a change if the College was to progress. Accordingly, in 1941, Holland was replaced as rector, though he continued to teach in the high school.

|

| St. Paul's with extended Paul Shea Hall |

Abiding Spirit

John Holland had proven to be a second founder of Saint Paul’s. Despite several changes in leadership and personnel, the good spirit which he painstakingly cultivated continued to characterize the College and High School. The reports of visitations from the late 1950s testify to this fact. In 1955, Provincial Superior George E. Nunan, wrote to General Superior Jean-Baptiste Janssens, that:

“The fidelity of the members of the Community to spiritual duties and their generosity in doing the work assigned them is gratifying. For these divine blessings and that of mutual union, the Community should be thankful to God.”

And in 1957 Nunan said: “the charity and zeal of the members of this community is remarkable.”

Father St. Clair Monaghan, the principal of the High School, observed that “the spirit of union and religious charity existing in the community is worthy of praise and commendation.” Clemens J. Crusoe noted that “ the community’s spirit of good will and basic contentment is reflected in their work.” In 1958, future librarian Father Harold J. Drake said, “Our community here is considered to be one of the luckiest and happiest ones in the Province.”

In their reports from 1956 to 1958, Fathers Nunan, Crusoe, and Sheridan praised the High School Principal, Father Monaghan, and his assistant, Father Barry Connelly, for their “firmness in direction of studies and discipline.” Father Clarence Lynch, assisted by Jesuit Scholastic (seminarian) John English, had obtained good results with religious sodalities. And Crusoe defined Father Hanley’s course in speech as “outstanding.” Sheridan observed that the boys, who were observing a stricter dress code of jackets and ties, manifested “a more serious approach to studies and a wider interest in things spiritual.”

Old Wine in New Wineskins

Archbishop Sinnott did not live to see his vision for Saint Paul’s become a reality. In 1954, the year of his death, the University of Manitoba extended an invitation to relocate to its Fort Garry campus, offering cost free land on a renewable 99 year lease. The College would have to find the money to construct a building. After much discussion, in the spring of 1956, the Jesuits accepted the offer.

In order to ensure the future of the College, on 18 May 1956, several Jesuits, led by College Rector Cecil C. Ryan, asked the General Superior for permission to establish a lay advisory board. This was to bring prestige to the institution by the association of prominent citizens, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, from Winnipeg business and professional sectors. In addition to funds received from private donors, the Province of Manitoba provided $100,000 toward the construction of the new Saint Paul’s.

|

| Cecil Ryan, SJ |

In fact, Ryan’s term had already been extended a year to oversee the completion of the new College. The new Provincial Superior, Father George F. Gordon, obtained further permission to delay the announcement of the new rector until after the opening ceremony, because Pocock wanted Ryan remain in office until that event took place. In a report to the General, Gordon described the October 1958 inauguration as “a very notable event in the history of Catholic education in Canada.”

In 1964, the High School relocated to its a new building of its own, taking with it the painting which Pius XII gave Archbishop Sinnott for Saint Paul’s. Originally displayed in the main foyer, it has since been moved to the entrance of the new chapel. Bartolommeo della Porta’s renaissance original has been located in the papal antechamber, the Sala del Tronetto, where it hangs on the oppose wall of the artist's painting of his fellow apostle of Rome, Saint Peter. Documents pertaining to the Winnipeg copy were discovered in the Vatican Apostolic (formerly know as the “Secret”) Archive, only weeks after the papers on Saint Paul’s were unearthed in ARSI.

Father Holland’s Corner

Father Drake wrote that “the story of Saint Paul’s is a good one, and has to be told.” The same goes for the story of its refounder and his Jesuit team. The decision to appoint Holland to lead Saint Paul’s was fortuitous. He began his mission by accompanying young men in a search for wisdom to its Source. And in retirement, he continued to accompany alumni and friends and share news, making use of his prodigious memory. His care for the Saint Paul’s family, past and present, was epitomized in his column, “Father Holland’s Corner.”

h

h